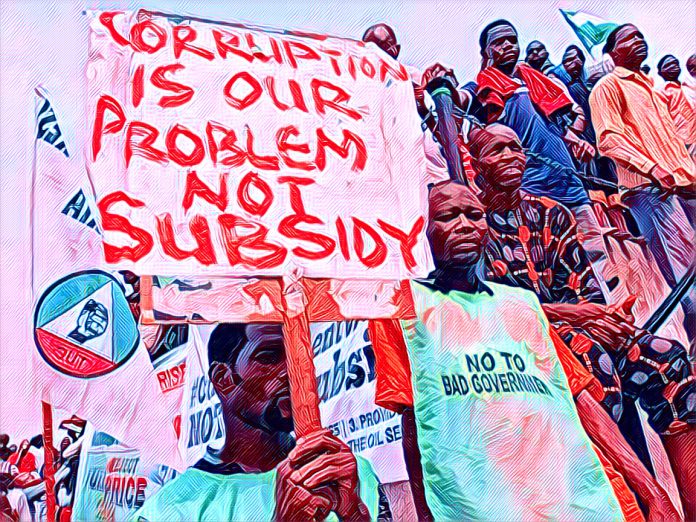

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation and largest economy has long been plagued by corruption, which undermines its development and democracy. According to Transparency International, Nigeria ranked 149 out of 180 countries in the 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index, with a score of 25 out of 100.

The Nigerian government has repeatedly declared its commitment to fight corruption and has established several agencies and laws to combat the menace. However, civil society groups in the country have questioned the effectiveness and impact of these efforts, saying that there is little evidence of progress or results.

CSOs demand accountability and transparency

On Tuesday, a coalition of civil society organizations (CSOs) met with representatives of government anti-corruption agencies in Abuja, the capital, to present their report on the Civil Society’s Monitoring Mechanism for Nigeria’s Implementation of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC).

The UNCAC is a global anti-corruption treaty that covers a wide range of issues such as prevention, criminalization, international cooperation, asset recovery, and technical assistance. Nigeria ratified the convention in 2004 and has participated in its review mechanism since 2010.

The CSOs, led by the Centre for Fiscal Transparency and Integrity Watch (CeFTW), said they had developed a tool to independently monitor and evaluate Nigeria’s compliance with the UNCAC, using data from official sources, media reports, and surveys.

The report, which covered the period from 2017 to 2023, revealed that Nigeria had failed to fully implement many of the provisions and recommendations of the UNCAC, such as setting up an inter-ministerial committee to coordinate the national anti-corruption strategy, publishing a report on the financial audit of political parties, and ensuring the independence and autonomy of anti-corruption agencies.

The CSOs also criticized the lack of transparency and accountability in the allocation and expenditure of funds by anti-corruption agencies, saying that there was no clear link between the resources spent and the outcomes achieved.

“It is not enough that we continue to spend resources on anti-corruption agencies and activities, but such expenditures must lead to a verifiable reduction in corruption,” said Umar Yakubu, the executive director of CeFTW and the sub-Saharan Africa representative on the UNCAC board.

Anti-corruption agencies defend their performance

The meeting was attended by officials from the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC), the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), the Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB), the Code of Conduct Tribunal (CCT), and the Federal Ministry of Justice.

The anti-corruption agencies defended their performance, saying that they had made significant achievements in the areas of prevention, investigation, prosecution, and recovery of stolen assets.

They also highlighted the challenges and constraints they faced, such as inadequate funding, legal bottlenecks, political interference, and public apathy.

The acting chairman of the ICPC, Dr Musa Aliyu, said the commission had the mandate of tackling corruption in the public sector, with a major focus on prevention.

He also said the ICPC had launched several initiatives to promote integrity and accountability in the public service, such as the National Ethics and Integrity Policy, the Anti-Corruption and Transparency Units, and the Constituency Projects Tracking Group.

The EFCC, which is the main agency responsible for investigating and prosecuting financial crimes, said it had secured over 3,000 convictions and recovered over N1 trillion ($2.5 billion) in the last six years.

A long way to go

The CSOs and the anti-corruption agencies agreed that there was a need for more collaboration and dialogue to enhance the implementation of the UNCAC and the national anti-corruption strategy.

They also called on the government to ratify and implement other relevant international instruments, such as the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption, the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, and the Open Government Partnership.

Nigeria’s anti-corruption war is far from over, and the country still has a long way to go to achieve its vision of a corruption-free society. However with the active participation and oversight of civil society groups, the government may be held more accountable and responsive to the expectations and aspirations of the people.

Source: Vanguard