The concept of immunity for government officials, enshrined in the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, was initially designed to shield the president, governors, and their deputies from lawsuits during their tenure, allowing them to focus on governance without the distractions of litigation. Section 308 of the Constitution explicitly protects these officials from civil or criminal proceedings, arrests, and any court process that compels their appearance. This legal buffer is meant to foster uninterrupted state management and decision-making aimed at delivering the dividends of democracy.

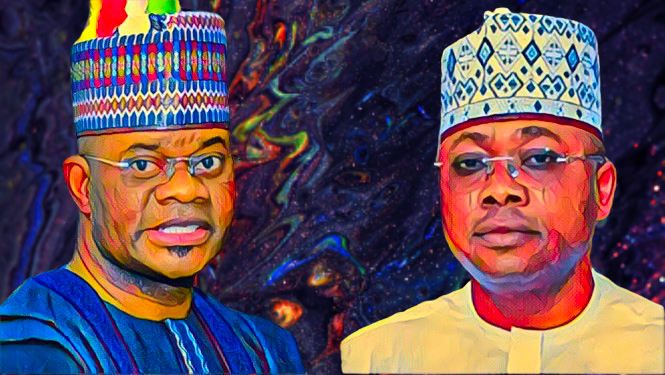

However, recent events have starkly highlighted how this protective measure is increasingly being manipulated as a shield for misconduct, leading to a widespread debate about its potential reform. The unfolding drama involving Yahaya Bello, the former governor of Kogi State, serves as a poignant illustration. In April 2024, Bello was sought by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) on allegations including money laundering amounting to N84 billion. Efforts to apprehend him were thwarted by a dramatic intervention by the current Governor of Kogi State, Usman Ododo, who reportedly facilitated Bello’s escape from his residence, exploiting his immunity to bypass the EFCC’s operation.

This incident is not isolated. Similar scenarios have occurred in the past, where governors have obstructed justice under the guise of their constitutional immunity. In 2017, Ayodele Fayose, then Governor of Ekiti State, intervened to prevent the arrest of Apostle Johnson Suleiman, who faced allegations of inciting violence. Similarly, in 2020, Governor Nyesom Wike of Rivers State halted the arrest of Joy Nunieh, the former Acting Managing Director of the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC), who was embroiled in a controversy with the Minister of Niger Delta Affairs, Godswill Akpabio.

These actions raise critical questions about the balance between protecting high-ranking officials from frivolous lawsuits and preventing the abuse of power. Public affairs analyst Bola Bolawole and legal expert Mohammed Ndarani argue that the immunity clause, while well-intentioned, has been perverted into a tool for evading accountability. Bolawole points to the stark contrast in responses by officials when faced with legal challenges—some choose to confront the allegations head-on, as Fayose did by voluntarily appearing at the EFCC office in 2018, while others, like Bello, evade the law.

The call for revising the immunity clause is growing louder among legal scholars and the public. Ndarani views it as an “open invitation to impunity” that ultimately harms the nation by allowing unchecked executive actions that can destabilize the political, economic, and social fabric of society. Conversely, Ebun-Olu Adegboruwa (SAN) notes that while the immunity is temporary, lasting only during the tenure of the officials, the potential for its abuse necessitates stringent post-tenure accountability mechanisms.

The debate extends beyond legal circles to the grassroots level, where citizens express growing disillusionment with their leaders’ ability to govern without self-interest. The EFCC’s ongoing struggles to bring former governors to justice underscores the broader challenges of combating corruption within a system that inadvertently protects the very individuals it should regulate.

In conclusion, while the immunity clause was established to protect governance from legal distractions, its current application raises significant concerns about its role in fostering impunity. With mounting examples of misuse and public outcry, there is an urgent need for a balanced approach that safeguards the intent of the law while ensuring that it does not serve as a blanket shield for malfeasance. This may involve amending the clause to limit its scope, implementing stronger checks on its application, or enhancing the transparency and accountability of those in power. Only through thoughtful reform can the spirit of the law be preserved, ensuring it supports governance that is both effective and ethical.